I just have to say it. SaaS sales compensation is not nearly as complex and mysterious as it has been made out to be. I’ve read so many discussions on SaaS sales compensation that claim you should do this in one case and that in another case, such that by the time you finish you can’t see the forest for the trees. Since I’m in the middle of this series on SaaS metrics, it seems high time I got around to addressing this topic (which I’ve been avoiding simply because I did not want to plant yet another tree).

So, here is the scoop….

| The ONLY difference between SaaS sales compensation and sales compensation for software or other products is that you should pay based on the LIFETIME VALUE of THE DEAL instead of the unit price of the product (there being no unit price). |

Wait! Relax. Although at first glance, lifetime value may appear to be an overly complex metric to use for sales compensation, it is always proportionate to recurring revenue. So, you simply have to replace “price” with MRR or QRR or ARR in your favorite sales compensation model and you are fine. That’s it! Now you can apply any of the various sales compensation models that you already know and love. Your particular choice should match the specific goals, products, pricing and culture of your specific business, as with any other sales compensation design challenge.

The primary principle of sales compensation is to pay the sales rep in proportion to the value of the deal, usually measured by the price of the product. The value of the deal in turn is wrapped up in the sales commission percentage, which is calculated by dividing the target commission at quota by the sales rep quota:

commission % = target commission at quota / quota

The quota in turn is determined by what is achievable for such a sales rep in terms of number of deals and the average deal value.

quota = target # of deals x average deal value

And, the actual sales compensation is calculated by multiplying the commission percentage by the actual sales.

sales compensation = commission % x actual sales

The target commission is determined by the labor market rate for the type of sales rep you need to fulfill the sales role. This is important, because it is at this point in the sales compensation plan design that we clearly see that sales compensation is NOT about paying the sales rep a percentage of revenue, it is about allocating a target commission payout based on a measure of performance (quota). The measure we use for performance (license revenue, recurring revenue, margin, etc.) is completely arbitrary. We consciously choose a measure that scales with deal value, so that sales compensation aligns sales rep performance with company performance.

You can get really fancy with tiers, spiffs, margin vs. revenue, etc., but these basic formulas are the cornerstone of any sales compensation plan, and this does not change for SaaS. What does change is how you measure deal value, and thus the relevant measure of sales performance.

In a subscription business with a recurring revenue stream, the value of the deal is not as clear cut as the price of a software license. As any MBA or bond trader will gladly tell you, the true value of a subscription deal is the present value of the future cash flows, which amounts to summing up all the recurring revenue over time, taking into account churn, and discounting it by your cost of capital. For a simple subscription with constant recurring revenue, “RRâ€, this is given by the following formula:

SaaS Subscription LTV = RR + RR (1 – a)/(1 + i) + RR [(1 – a)/(1 + i)]^2 … RR [(1 – a)/(1 + i)]^N

SaaS Subscription LTV = RR ( 1 + i ) / ( i + a )

Where “i†(for interest) is the cost of capital and “a†(for attrition) is the churn rate, and N is the number of payments made over the customer’s lifetime. If the customer follows the normal churn rate, the top LTV formula simplifies to the bottom LTV formula. Again, the MBA’s in the audience will recognize this as the formula for the present value of an annuity.

I say again….do not fear! As previously mentioned, the LTV of the deal is always proportionate to recurring revenue of the deal. The salient word here being “proportionate.†When it comes to designing our SaaS sales compensation plan, we can use ANY measure of recurring revenue (MRR, QRR, ARR) that is proportionate to lifetime deal value. We do not need to calculate the absolute LTV for the deal, because the commission percentage will scale up or down as needed to make sure we payout the target sales compensation. Thus for SaaS, we simply change the calculation to the following:

SaaS commission % = target commission at quota / quota in recurring revenue

SaaS quota = target # of deals x average deal value in recurring revenue

SaaS sales compensation = commission % x actual sales in recurring revenue

Recurring revenue can be measured monthly, quarterly, or annually, because the sales commission percentage scales accordingly. But, once a time-frame for recurring revenue is chosen for calculating the sales commission percentage, it is critical to stick with the same recurring revenue time-frame throughout your SaaS sales compensation plan, i.e., if you calculate average deal value and quota in ARR, then you must measure actual sales in ARR as well to get the correct actual sales commission payout.

Failing to stick with the same recurring revenue time-frame throughout creates an expensive bait-and-switch problem that is the root cause of SaaS Sales Compensation Mistakes 1 & 2 below. Psychologically it is often best to base your SaaS sales compensation plan on a recurring revenue time-frame (monthly, quarterly, or annually) that equals your most common contract renewal term, e.g., if you mostly sign annual renewal contracts, then base your sales compensation plan on ARR, if most renewal contracts are monthly, then use MRR.

To recap…replace unit price with MRR/QRR/ARR…done.

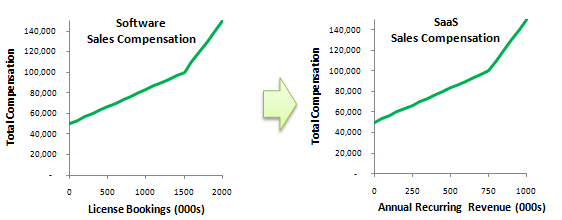

The picture above shows a quick visualization for two sales compensation plans for two sales reps with similar skill sets and market labor rates: one at a software company, and another at a SaaS company. In both cases, the sales rep has a base salary of $50K. On the left, the goal is to motivate the software sales rep to bring in $2M in license revenue. The software sales compensation plan has an accelerator such that payout is $100K at $1.5M and $150K at $2M, and unlimited upside if the sales rep can blow it out of the water.

On the right is a SaaS sales compensation plan where the goal is to motivate the SaaS sales rep to bring in $1M in annual recurring revenue. The plans are IDENTICAL except for the scale of the performance measure on the x-axis (swapping license price with ARR). The SaaS sales compensation plan has a base pay of $50K and an accelerator such that the payout is $100K at $750K ARR and $150K at $1M ARR, and again with unlimited upside to motivate your top sales performers. If we want to recast the SaaS sales compensation plan from ARR to MRR or QRR, we simply change the scale of the x-axis by calculating average deal value, target quota and actual sales in MRR or QRR, 1/12 or 1/4 of ARR respectively.

OK. Visual, but maybe not so easy. Below is a simple numerical example that walks you through the calculation.

SaaS Sales Compensation Plan – Easy Example

Consider a SaaS sales job that requires a skilled sales rep in the $100K range. Say $50K commission + $50K base. What quota can the sales rep carry? Say 5 deals/month at an average deal value of $1000 MRR (equivalent to $12,000 ARR). Using the SaaS sales compensation formulas above with MRR as the measure, the quota in MRR is calculated as follows.

SaaS sales quota = 60K MRR per year = 5 x 12 x $1000 MRR

The SaaS sales commission percentage is then…

SaaS sales commission percentage = 83.33% = $50K ÷ $60K MRR

Now, lets see what happens when our SaaS sales rep closes three deals. A monthly renewal contract with a $1000 recurring payment, an annual renewal contract with a $12,000 recurring payment, and a two year renewal contract with a $24,000 recurring payment. All three deals have an IDENTICAL deal value of $1000 MRR, so our SaaS sales compensation plan will pay them all at an IDENTICAL sales commission.

SaaS sales compensation payout = $833.33 = 83.33% x $1000 MRR

This SaaS sales compensation math is straightforward and really easy for the sales rep to track…no spreadsheet required. For example, here is the list price MRR for all sf.com editions.

For comparison, here is the EXACT same SaaS sales compensation plan and sales commission payout for the deals above recast in ARR.

SaaS sales quota = 720K ARR = 5 x 12 x $12,000 ARR

SaaS sales commission percentage = 6.944% = $50K ÷ $720K ARR

SaaS sales commission payout = $833.33 = 6.944% x $12,000 ARR

This example should make it clear that the choice of MRR, QRR or ARR is completely arbitrary, because the SaaS sales commission percentage scales accordingly to pay the same actual sales commission for the same actual deal value, regardless of which recurring revenue time-frame you choose. The only important rule is that you must use the same recurring revenue time-frame throughout all your SaaS sales compensation plan calculations.

This is where SaaS Sales Compensation Mistakes #1 & #2 below rear their ugly heads. When it comes to payout, there is a tendency to want to swap out the correct recurring revenue measure for the explicit contract renewal payment. For example, in the ARR plan above to plug in $24,000 for the 2 yr deal and pay out $1666.67 instead of $833.33. Don’t do it!

The reason the monthly, annual and 2 year renewal contracts all pay the same commission amount is that they all have roughly the same lifetime values, and are therefore of equal value to the SaaS company. The difference between the three is only the cost of capital. But, the rep and sales manager never see this. That is the point of using MRR/QRR/ARR as surrogates for LTV…to remove all the complexity.

Let’s say we have a churn rate of 10% and a cost of capital of 25% (typical for venture investment). The LTV of the three deals can be calculated using the second LTV formula above.

- 1 mo renewal contract LTV = $37,032

- 1 yr renewal contract LTV = $42,857

- 2 yr renewal contract LTV = $49,834

Sometimes longer term contracts may imply lower churn rates, if we assume 15% churn for the monthly contract and 7.5% churn for the 2 year contract we have the follwoing LTVs:

- 1 mo renewal contract @ 15% churn LTV = $31,618

- 1 yr renewal contract @ 10% churn LTV = $42,857

- 2 yr renewal contract @ 7.5% churn LTV = $53,050

These actual lifetime deal values differ by about +/- 25% (on the order of the cost of capital). They do not differ by 1/12X , 1X and 2X respectively. Hence, if we want to add an incentive to our SaaS sales compensation plan for signing longer renewal term contracts it should be determined by how much we value cash up front, i.e., the cost of capital. In the second example, you might penalize monthly contracts by 25% while placing a 25% premium on longer 2 yr contract, paying $625 for the monthly renewal contract and $1050 for the 2 year renewal contract. You would not pay 1/12X and 2X respectively.

Note: If you have customers with dramatically different churn profiles, you should segment these deals and prorate commission payment relative to the norm as in the second example..

Since this post was published, I created a saas sales commission spreadsheet that demonstrates these calculations.

In Summary

Basing your SaaS sales compensation plan on MRR/QRR/ARR is not about cutting commissions off at one month/quarter/year. MRR/QRR/ARR are used because they are all equally good, simplified measures of LTV. Paying on MRR/QRR/ARR ensures that the sales rep is paid in-full, up-front for the full lifetime value of the deal that has been closed, regardless of the payment plan chosen by the customer. Not some underpayment or overpayment spuriously based on the contract renewal term, and not in dribbles over the life of the contract to match cash flow. Good for the SaaS sales rep. Good for the SaaS business. Good SaaS sales compensation plan design.

How much easier could it be? Well…here are some very common mistakes to avoid.

SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #1

Paying SaaS sales compensation on explicit total contract value

Happy customers renew their contracts. Unhappy customers don’t. Unhappy customers cancel early, and ask for refunds. If your customers are happy, then the primary benefit of a long term contract is up-front cash payment, not lock-in. Happiness = Lock in. Your SaaS sales compensation plan should reflect this reality. Consider a service that costs $100/month. A monthly renewal contract appears to be worth $100, while a 1 yr renewal contract appears to be worth $1200, and a 2 yr renewal contract appears to be worth $2400. In reality, all three contracts have the same recurring revenue ($100 MRR or $1200 ARR), and should therefore pay the same baseline commission. This is the essence of Bessemer Law for being SaaS-y #1, which states that “bookings are for suckers.”

Longer term contracts are worth more, but the difference in value is your cost of capital which is typically in the 5-30% range depending on your source of funding. The financially sound SaaS sales compensation approach is to pay a baseline commission on the recurring revenue of the deal, then provide an accelerated payment incentive for longer contracts in the 5-30% range that reflects your own cost of capital. (See the numerical example above for a more detailed explanation). If you base your SaaS sales compensation plan on ARR, then sign a 2 yr contract and foolishly plug the explicit contract value of $2400 into your SaaS sales compensation payout formula because the deal FEELS like it is worth $2400, then you are paying as if the deal was worth twice as much. It isn’t.

SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #2

Trying to manage cashflow through your SaaS sales compensation plan

This is the reverse bait-and-switch of SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #1 above, arising when you sign contracts with short subscription terms, e.g., monthly. In this case, there is a tendency to not what to pay out sales compensation in advance of receiving payment. Tough! It isn’t the sales rep’s job to manage cash flow. It’s the sales rep’s job to bring in the deal. If your customers are happy, then a monthly payment plan is just as valuable as an annual plan, minus a small percentage for the time value of the money. The best approach is to pay the sales rep in-full, up-front based on the recurring revenue, then tack on a 5-30% penalty for short term contracts as described in SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #1 above.

If you are one of those lucky SaaS companies that has high early churn and then things settle down, you might want to break the payment up into two, e.g., 50% now and 50% when things settle down. But, you should NOT leave the sales rep waiting and waiting to get paid over time in an attempt to match cash flow to sales compensation. If your churn rate is very very high, say 50%, then you might ask yourself if you are in a recurring revenue business in the first place and simply revert back to paying on actual contract value.

SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #3

Not including fully loaded sales compensation in customer acquisition cost

Customer acquisition cost should include all the labor it takes to get a new customer signed, not just out of pocket sales and marketing costs. Generally, adding up all sales and marketing expenses is the best way to calculate your customer acquisition cost. This way you don’t miss anything. When you do this, you will almost certainly find that fully loaded sales compensation costs are a dominant contributor to total customer acquisition cost. As indicated in the SaaS metrics series, controlling acquisition costs is a critical factor in reaching profitability. Therefore, it is important to set a target for the ratio of fully loaded annual sales compensation to new annual recurring revenue that gives a sales contribution sufficient to support overall business profitability (i.e., sales contribution = 1 – sales expense ratio).

SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #4

Not scaling sales compensation with sales productivity

Some good benchmarks to plug into the commission formula above are $100K in total sales compensation for $1M ARR. On a 50:50 split, this gives a commission percentage of 5%. But, what if you are a start-up and a quota of $1M ARR is just plain unachievable? For example, if your current average deal size is $1000, your sales rep would need to close 1000 deals/year! In this case, you might need to pay 20% on a quota of $250K ARR just to get your business off the ground. However, a sales contribution of 60% is unlikely to be profitable in the long run, because you are paying $100K in sales compensation for a measly $250K ARR (i.e., 60% = 1 – 100K/250K). In this scenario, you should work hard to increase both your average deal value and your achievable quota. As you grow, it is important to scale your commission percentage in lockstep with your increasing achievable quota, otherwise you will get locked into a low sales contribution percentage that will sink your long term profitability.

[…] can be closed by an upgrade or upsell, then you should hunt it down and sell it. And, you should compensate sales reps for the incremental recurring revenue. If upgrades and upselling are constrained by your customer’s current state of growth such that […]

In the plan you describe, would you pay commission on the setup fee a customer pays or just the recurring revenue? Thanks!

[…] explanation of how to think about this topic I’ve seen, in a blog post by Joe York – click here (warning: this one is pretty […]

[…] cluttering up this article with. It’s different in a SaaS environment (where you typically compensate on MRR/ARR and make that your target), and yes, there are cases where you may not compensate on […]

[…] offering a software as a service solution at a lower monthly rate, say $50 per month, then a new commission structure based on the lifetime value of that client should be […]

What happens if you have an ARR that is based on estimated customer performance, for example you believe based on customer usage estimates that the ARR is $100K and you pay the sales rep commission on $100K, what if what is actually realized is $50K a year later, do you reconcilie the commission paid on the inital assumed ARR with what was realized? It seems that all commission plans designed by sales reps (and not finance) want to pay commission on bookings and don’t take into account what actually was realized.

Hi Rob,

I’m not quite sure about the scenario you describe. How would you think it is going to be 100K and then have it only be 50K?

Is this a usage based pricing model, such as AWS? If it is typical SaaS subscription, the 100K would be in a contract of some sort: monthly, quarterly or annual.

At any rate, the answer is yes. What I have seen work well is to pay up front, but then to ‘claw back’ the commission if the first year revenue is less than the expected ARR. For example, if the customer signs a quarterly contract and then cancels after two quarters, then the amount would be deducted from the reps most recent commissions at that time.

Note that one year revenue == ARR, so if you gear everything toward ARR, e.g., cost of sales is 90% ARR, then you can at least get some guarantee in the first year. Of course, this fails if the rep quits or the customer leaves 1 year and 1 day after signing up—but, you have to draw the line somewhere. My main point still holds; the primary risk should be born by the business, not the sales rep.

Cheers,

Joel

[…] https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-compensation-made-easy/ https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-commission-calculator-for-long-term-contracts/ […]

[…] More Resources on What are the disadvantages of offering a Freemium model for B2B SaaS software: http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saas-economics-1/ http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saas-economics-2/ http://www.bridgegroupinc.com/resources.html http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/blog/ https://chaotic-flow.com/ http://www.slideshare.net/MassTLC/110201-sales-comp-ppt http://www.netcommissions.com/blog/ https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-compensation-made-easy/ […]

[…] More Resources on What are typical commission rates for SaaS sales people: http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saas-economics-1/ http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/saas-economics-2/ http://www.bridgegroupinc.com/resources.html http://www.forentrepreneurs.com/blog/ https://chaotic-flow.com/ http://www.slideshare.net/MassTLC/110201-sales-comp-ppt http://www.netcommissions.com/blog/ https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-compensation-made-easy/ […]

Very good blog! Do you have any tips and hints for aspiring writers?

I’m hoping to start my own site soon but I’m a little lost on everything.

Would you advise starting with a free platform like WordPress or go for a

paid option? There are so many choices out there that I’m completely confused ..

Any ideas? Many thanks!

[…] explanation of how to think about this topic I’ve seen in a blog post by Joe York – click here (warning: this one is pretty […]

Thanks for giving this article. It really helps build a total picture of compensation plans.

In the LTV part, I had problems with calculating 1mo, 1yr, 2yr renewal LTVs based on annuity. Please help by giving one calculation example.

Thanks.

Hi Richard,

See this post.. https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-commission-calculator-for-long-term-contracts/?show=comments#comments

Between the spreadsheet formulas and the comments, I think you will get what you need.

Cheers,

Joel

[…] https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-compensation-made-easy/ https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-sales-commission-calculator-for-long-term-contracts/ […]

Joel,

Thank you for the education!!

As a software license guy getting his hands around SaaS, you laid it out logically. I’m heading up sales for an early stage 1 year contracts (as we’re VC funded. Does that sound like I get the gist?

Robert

THANK YOU! THANK YOU! THANK YOU! THANK YOU!

I just found your site! Let me re-phrase that; The Lord God, Almighty directed me to your site! I’m in a contract negotiation with a SaaS firm. They’ve charged ME with the design and implementation of my OWN compensation plan. This, to me, is somewhat of a breach of protocol…The went straight to the “DOUBLE DOG DARE”, as it were!

I’m a sales rep and have suffered many, many different comp plans. My friends and I would laugh when any CEO would announce a “new and exciting comp plan and YOU GUYS ARE GONNA LOVE IT!” This invariably meant; “We’re paying you guys wayyyy toooooo much and we’d like to keep some of that cabbage you’ve been stealing from us.”

A past CEO, Howard Solomon from Forest Pharmaceuticals (NYSE; FPI) had the dubious honor of being named Forbes “Worst CEO” for highest salary/worst return to shareholders after restructuring our comp plan several times in a year. Howard actually paid a consultant $250,000 to divine “Why”…Why, oh, why do so many of our reps leave us after such short employments after we arduously interview, hire, and train them.” The consultant came back with “Mr. Solomon, you have the highest, largely unattainable, unrealistic quotas and lowest pay scale in the entire pharmaceutical industry.” The man was apparently shocked we weren’t more loyal…after all; we each got a new Ford Taurus every three years! I attained pharmaceutical sales Nirvana while there. I grabbed a 33% market share with several of our “me too” drugs. In that industry, a 27% to 33% share amongst a multitude of “also-rans” pretty much makes you the king…or queen of your territory. My final quota, on all six (most drug reps marketed two, three prescription drugs…tops) of my drugs was 66%! Meaning, I had to double my quota- smashing efforts to get paid dollar ONE of commission from Forest Pharmaceuticals moving forward. They essentially said “You’re getting your base salary from now on… DEAL with it!”

I had to file suit years ago because the new owner of a 20 year old business, an inherently greedy, evil troll of a man, was both amazed and disgusted at how fast I made deals happen. Amazed…over 1000% revenue increase in one FY; disgusted because this textbook “Horrible Boss” decided to fire instead of paying my six-figure commissions. He thought the monster accounts I brought in were enamored with his product. I won my suit handily because of excellent documentation and took the aforementioned monster accounts with me! The troll had just signed leases for additional physical plants to handle the monster accounts. The square footage the jackass leased for five years was TEN times the size of the place when I started! He went out of business.., and was declared financially, as well as spiritually bankrupt.

I don’t care to go through that ever again. It was a soul-crushing e experience! My greatest financial coup and proudest accomplishment sullied by the boundless greed of a hideous, hateful wart of a man. But I digress; I need a mutually understood contract and commission structure with long term payouts. In any case, the information I’ve found on this site is PRICELESS! So, I want to extend my heartfelt, ENORMOUS thanks.

Thanks for the detailed article. This is a big help for us to try and structure a basic sales compensation plan as we move from an ISV to a SaaS business model.

i am just saying thank you Joel.

i have learned too much from your blog. god bless you. 🙂

this comment is not only for this post, it is for the whole blog.

Hesham

[…] my post on SaaS Sales compensation, I made the claims that SaaS vendors should a) pay in proportion to the lifetime value of the deal […]

Joel,

Great article, thanks.

We’re moving from a license/maintenance model to a SaaS model, using the same sales reps, and to goal them with the same “on-target earnings” (OTE) means that commission rates will be much higher as a result of quotas being necessarily lower (say using ARR). Of course we could artificially remedy that by using a multi-year RR, but the really key issue we need to deal with is the company cash flow (float) issue that with annual upfront RR payments on our contracts, it is 3+ years before we realize the same cash from the customer as we would have under the license/maintenance model. Yet you advocate paying the rep basically the same upfront even though our initial payment sizes are decreasing dramatically.

Have you implemented, or observed any good models for trying to match cash flow of sales rep payments with inbound cash flow from customer? Without creating the “account management syndrome” you referred to in a response to an earlier comment, that is.

I’ve been thinking about doing something like the following:

1. Calculate the commission based on your model.

2. Pay say 65% of the commission at the time the deal is closed.

3. Pay say 25% of the commission on the first anniversary of the deal closing (which often will coincide with the customer renewal, but not always as we sometimes do initial subscriptions shorter than a year to allow customers to get started when they hadn’t even budgeted for a solution like ours in their current fiscal year).

4. Pay the final 10% of the commission on the second anniversary of the deal closing.

The rep would have to still be employed on the anniversaries to get the follow on payments, which creates a bit of a retention strategy. I had been contemplating also making the follow on payments contingent on the customer renewals, but to your point about not creating the “account manager syndrome”, it might be better to not make them contingent on the renewals – just purely a timing issue. I think perhaps using the penalty commission calculation you propose for deals that cancel in less an a year, or initial deals of less than a year that don’t renew is probably the best approach.

I think the reps could understand and even appreciate the issue we’re attempting to deal with, especially since they at least get disproportionate payment in the earlier years on each deal, even though the company’s payment is even over the years. Of course, for a rep making their on-target commission under the license/maintenance model last year, moving to a model this year where they only get 65% if they achieve their quota and have to wait for the rest won’t be desirable from their perspective. But in their second year under this model, if they’re making their quota, then they’ll get 65% in year 2 and 25% from the year before, so 90% in total. And then by year 3, they’ll be at 100%. And in years they underperform, they’ll have some carry forward from prior years.

Any other thoughts or pointers to models where companies have matched their inbound cash flow with outbound cash flow to reps would be appreciated.

Thanks

Mark.

Hi Joel,

We are moving from our original “license fee year 1 and 20% support and maintenance in subsequent years” model over to per user per month SaaS model (breakdown below).

On face value I think this may be viewed as a little one sided (in favour of the company)!

Scenario if a sale costs $20K upfront commitment 1 year, $40K upfront commitment 2 years and conversely $60K for upfront commitment 3 years on the following model the sales person would make an additional $800 (because it is only based on the first 12 months) whilst the company gets to realise the full additional $40K on a pay upfront 3 year signing:

PAYG 8% of first 12 months revenue

12 mts upfront 11% of first 12 months revenue

24 mts upfront 13% of first 12 months revenue

36 mts upfront 15% of first 12 months revenue

I would appreciate your thoughts as I have given my initial feedback that I do not think this will be viewed as favourable for sales people to try to get clients to agree to a long term commitment/upfront cost if the return is so limited.

Very best

CJ

Hi CJ,

The numbers are not unreasonable if they fit the business. First and foremost, your renewal rates must be strong, so that you are truly in a recurring revenue business. I did a little “what if” analysis using my SaaS Sales Commission Calculator for Long Term Contracts. Here is a scenario that fits this payout:

Giving the following…

So, the sales commission would reflect the value to the company in this scenario. However, I agree that it is unlikely to motivate sales to “get clients to agree to a long term commitment.” What I suggest is to leave it up to the customer. In this plan you could offer a discount to the customer of up to 25%, 35% and 45% off the monthly price for customers that sign annual contracts (or equivalently a premium of 35% on monthly, and discounts of 15% and 25% on 2 yr and 3yr contracts relative to a standard annual contract price). With this approach, the sales commission is “contract neutral”, i.e., the sales person is paid about the same regardless what length contract is signed. The customer, however, now has a strong direct incentive to sign longer term contracts without feeling manipulated by the sales rep. And, the sales rep has a new tool. When a customer asks for a discount, the rep replies “Sure, no problem, I can give you a discount if you sign up for a longer term contract.” And, you get something in return for the discount.

Cheers,

Joel

Thanks for the response and information. Much appreciated.

Cheers

Nick

Hi Nick,

You are correct. It is the renewal term that determines the cost of capital charge, not the contract term. In the post, I assume these to be equal for simplicity.

In your case, a discount for say a one year contract that is paid monthly would have to be justified by a lower average churn rate, i.e., customers that sign annual contracts have lower churn than those that don’t, so you have two churn cohorts based on contract type. You would need to run you own numbers to validate this hypothesis, because it is possible that you simply have a big drop-off of annual contract customers at the end of the year that is equivalent to the gradual drop-off of monthly customers.

At any rate, the formula you are looking for can be found in this follow-on post. SaaS Sales Commission Calculator for Long Term Contracts that includes a spreadsheet that you can use to compare renewal term and churn scenarios.

Cheers,

Joel

Hi Joel,

Thanks for the article. You have made an interesting assumption that doesn’t apply in my business. When a customer signs a 1 year or 2 year contract this doesn’t mean the customer pays up front on a 1 year or 2 years basis. So the cost of capital consideration doesn;t apply.

What do you propose for discounts or premiums on commision rates in this case? I think there is a benefit to having a customer commitment for a longer term (even when payments are monthly or quarterly), in that your contracting and sales costs are reduced.

thanks

Nick

Great article that provides a terrific explanation of sales compensation! It is usually very frustrating to convert sales compensation excel spreadsheets into individual pdf files. One program that I have found that makes this process easy can be found at

here

Joel,

Spot-on and very helpful, indeed. Just attended a conference on experiences in moving from license business to SaaS. Most of the vendors addressed exactly this issue.

Looking forward to reading more from you,

Michael

[…] my post on SaaS Sales compensation, I made the claims that SaaS vendors should a) pay in proportion to the lifetime value of the deal […]

this was good- thank you for your contribution.

[…] Calculator for Long Term ContractsBy Joel York on September 17, 2010 TweetSince my post entitled SaaS Sales Compensation Made Easy, I’ve received a number of inquires about how to adjust SaaS sales commission percentages for […]

Hi Joel,

Thanks for the information. We have a lower priced offering (average sale is worth $1,600 per year) and we pay a percent of total year one value. Under this model, what do you suggest as the percent range?

Note we want the salesperson paid off at time of sale and moving on to the next sale, and all sales are from inbound leads created from marketing.

Thanks,

Dave

[…] SASS and Cloud offerings require a bit more thought, although according to Joel York in his March 2010 article SaaS Sales Compensation Made Easy, “The ONLY difference between SaaS sales compensation and sales compensation for software or […]

Hi Chintan,

Let’s start with your last comment “there are no exit barriers for the customer.” There are ALWAYS exit barriers to the customer and they can usually be measured by the amount of customer data that is input into your system. See for reference

https://chaotic-flow.com/saas-economics-101c-saas-adoption-and-switching-costs-the-double-edged-sword-of-data/

I see that EazeWork does employee self-service and payroll, so I’m sure there are plenty of switching costs that get higher the longer your customers use your system. Sometimes new customers drop off quickly…let’s leave that aside and come back to it.

If you pay out 10% monthly, the incentive you create is to build a territory and then sit on it and collect pay for past performance. This is the reason to pay up front, so reps will move on and find the next customer. You can always assign current customers to account managers and pay on retention. If I understand your current plan correctly, I believe it will slowly transform sales reps into account managers as they acquire customers.

What I don’t see in your comment is your target commission or quota. The payout seems to be based on the common misconception that the commission rate is the independent variable in a sales compensation plan. It isn’t. The commission rate is dependent and equals the target commission at quota divided by the quota.

Let’s say you want to pay your reps 100K/year to bring in 45K MRR per year in recurring revenue on a 50:50 split. I’ll take your 100 USD MRR and 15 users as the average deal. This has an average deal value of 1500 MRR. So a Rep would need to close 30 deals per year. Is this reasonable? If not, then the quota needs to be adjusted down or up as required?

The reps commission percentage would then be 50% x 100K / 45K MRR = 111% (per MRR).

And, the 15 user deal would pay 111% x $1,500 = $1667. And, will take you two months to generate positive cash flow (which BTW you can help manage by paying commissions quarterly instead of monthly).

If three months down the line the customer adds 10 users, then this is a a new deal and should pay a commission on the incremental lifetime value of the deal. 111% x 10 x $100 = $1111.

This confusion arose in the first comment above. In sales compensation, you want to pay on the lifetime value of the DEAL…not the customer. The lifetime value of the customer is the sum of all the deals.

CLTV = Deal 1 LTV + Deal 2 LTV + …. + Deal N LTV

Sales comp is based on the deal. This encourages reps to sell upgrades and upsell new services.

Now lets revisit the exit barriers problem. Often new customers rapidly segment into two groups. Those that stay and those that cancel early. There are two ways to handle the cancel early customers, neither of which involve paying the rep month to month.

1) Wait a little while to pay the rep in full, e.g., if customers often leave in the first 3 months, then pay your reps quarterly. Or pay 50% initially, and 50% in 3 months. But, don’t keep paying indefinitely. That turns your sales reps into account managers.

2) Pay up front. And, then back it out of future commissions if customers cancel early. For example, if the typical 15 user customer above cancels after three months, then adjust the next commission payment for the rep by 50-80% x $1667 and take the money back as a penalty adjustment for early cancellation.

Lastly, it appears from your comment that on a $1500 MRR deal, your reps will make $1800 per year the first year and then another $1800 the next year, etc. I’m guessing most of the hard work to acquire customers is done in first year. Why would you wish to continue to pay the same amount for simply sitting on the account? My guess is that an account manager can manage 10x the number of accounts that a sales rep can acquire in a year. (300 vs. 30 in this example)

Hope this helps…

Joel

Hi Joel,

Confusion..

My Scenario is… Annual contract with MRR = 100 USD per user and initial sale had 15 users. The client also has selected the option to pay monthly. So as you are suggesting we start paying the sales guy (assume 10% commission) – 15x100x10% = 150 USD per month and avoid Mistake # 1. Here I am pegging the payout to MRR.

If 3 months down the line the customer adds another 10 users then the sales guys monthly payout becomes 25x100x10% = 250 USD (its another discussion whether he should get full credit for the additional users / upgrades or part of that should be split with the services delivery team).

But when I read your comment in Mistake # 2 section “The best approach is to pay the sales rep in-full, up-front based on the recurring revenue, then tack on a 5-30% penalty for short term contracts as described in SaaS Sales Compensation Mistake #1 above.” the confusion sets in. We are not paying the sales guy up-front and are linking to the way the customer is paying, it is in a way linking to the cash-flow but isn’t that what is logical.

What is the value of an annual contract when there are no exit barriers for the customer?

[…] SaaS model, then how to update your sales compensation plan might be on your mind. In that case, this recent blog post by Joel York at Chaotic Flow on “SaaS Sales Compensation Made Easy”… may come in handy. Just remember that for SaaS you really need to focus on keeping customer […]

I think this is a reasonable model for selling higher-priced SaaS offerings (eg, enterprise sales, etc), because you can just translate an existing working sales compensation model relatively cleanly.

I don’t think it holds for lower-priced offerings that really need to be driven via inbound marketing and sales, keeping acquisition costs low.

Joanna

Software-Marketing-Advisor.com

very logical – very clean description – nice work

Hi David,

Lifetime value in this case refers to the lifetime value of the DEAL, not the customer. You should only pay the rep on the incremental recurring revenue of the deal.

An initial sale of $1000 ARR should pay out on that, done. No future payments on anything after the contract is signed.

An upgrade should pay on the delta in recurring revenue from the upgrade, not the recurring revenue of the entire subscription. And, it should ONLY be paid to the rep that closes the upgrade. For example, if a subscription in $1000 ARR is upgraded to $1500 ARR, the payout should be on $500 ARR = $1500 – $1000.

Separating hunters from farmers is best when upgrade potential is low and/or unaffected by anything the sales rep does, e.g., upgrades only occur as customers grow their business. In this case, the primary goal after the initial sale is retention, not upselling…hence the farming.

If the primary goal after the initial sale is more selling, because upgrade and upsell potential is high and the rep can truly drive it, and you pay out as I describe, your hunters will go hunting upgrades. Mine do.

JY

Since I’ve seen sales reps throw away customers who were calling them to order upgrades, I insist on separating hunters from farmers. Those hunters may get a tail, but they will not be compensated on lifetime value, since they really have no interest in that lifetime value.

I was taught by sales that what you are suggesting here does not work.